Tonight at 8 p.m., the Eastman School Symphony Orchestra — comprised of first-year and sophomore musicians — gives it first concert of 2016. Neil Varon conducts, and the guest artist is Professor of Voice Jan Opalach — not singing, but reading Ogden Nash’s verses for Saint-Saens’s Carnival of the Animals. Popular works by Wagner and Beethoven round out the free program, taking place in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre.

The program notes for this concert follow:

Wagner: Prelude to Act III of Die Meistersinger

Wagner conceived the idea of a comic companion to the recently premiered Tannhäuser in 1845. Over twenty years later — after completing Lohengrin, the Ring Cycle and Tristan und Isolde — Die Meistersinger premiered in Munich in 1868. Several characteristics set Die Meistersinger apart from Wagner’s other mature works. It is the only comedy, and his only original story; it is set in a historically accurate time and place (as opposed to a mythical or sublime setting); and there is no evidence of supernatural powers or beings. The opera is a story about a guild of craftsman-like Meistersinger, or “Master Singers”, in medieval Nuremberg.

The Prelude to Act III introduces music from a Scene 1monologue by the protagonist, Hans Sachs, “Wahn! Wahn!”, and the chorale “Wittenburg Nightingale”, sung by a gathering of townspeople to greet Sachs in Scene 5. The music begins with a meditative G minor melody in the cellos, who are later joined by the violas and second violins. A modulation to G major is led by the introduction of the brass. The winds and strings trade romantic passages until the sudden fortissimo, marked ausdrucksvoll, which translates as “very expressively.” The prelude ends on a peaceful G major chord in the strings.

John Fatuzzo

Saint-Saëns: Carnival of the Animals

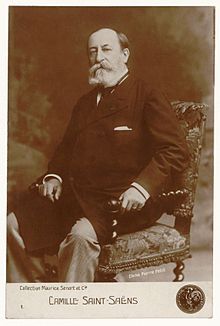

Camille Saint-Saëns would be dismayed, to say the least, that his most familiar piece has turned out to be a grande fantaisie zöologique which he wrote as a joke. Saint-Saëns wrote The Carnival of the Animals in February 1886. Its first performances were in private homes in Paris; it was not performed publicly until February 1922, although Saint-Saëns agreed to the publication of Le cygne (The Swan) in 1887. Since then, The Carnival of the Animals has become popular as a purely musical work, or with the addition of poems, such as the verses of Ogden Nash you’ll hear tonight.

Saint-Saëns offers fourteen, mostly very brief, movements:

Introduction and Royal March of the Lion. A pompous chromatic theme played by the strings over piano tremolos is followed by an equally pompous march. Listen for the lion’s roar in the lower strings.

Hens and Roosters offers a coq-a-doodle-doo, from clarinet, piano, and strings. Hémiones (or dziggetai) are wild Mongolian asses. As the pianists demonstrate, they are known for their speed. In Tortoises, the strings play Offenbach’s famous “Can-Can,” at a tempo befitting “turtley torpor,” to quote Ogden Nash.

The Elephant: double bass and pianos give the Allegro pomposo treatment to two gossamer tunes: Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream “Scherzo”; and the “Minuet of the Will o’the Wisps” from Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust. As Kangaroos, the pianists play “hopping” fifths at varying tempos and dynamics … and then hop away. In Aquarium, flute and strings float over cascades from the piano keyboards. Saint-Saëns also originally called for a glass harmonica – a set of glass bowls played by fingers dipped in water, a popular “at home” instrument. Its part is usually taken by glockenspiel or celesta.

Personages with Long Ears, i.e., donkeys, are represented by hee-haws in the violins. Are Saint-Saëns’s “personages” also certain music critics? He never said yes, or no. The Cuckoo (a very persistent clarinet) lives in the Depths of the Woods (provided by the pianos). Aviary presents more evocative, and virtuosic, flute music, this time evoking myriads of birds in a jungle. Pianists are apparently among the less intelligent musical animals, as the keyboard soloists lurch from playing C major scales to D-flat, to D, and to E-flat.

Fossils perform a mastodonal medley of such musical “fossils” as the French songs “Ah! vous dirai-je, maman,” “Au clair de la lune,” “J’ai du bon tabac,” and “Partant pour la Syrie”; “Una voce poco fa” from Rossini’s Barber of Seville; and Saint-Saëns’s own Danse macabre, in the bony tones of the xylophone.

The Swan is a perfect depiction of a swan (solo cello) on a calm lake (the rippling pianos). Pace Anna Pavlova, the dancer who made this music into a solo showpiece, the swan does not die, but merely glides away. The Finale is a real can-can. Several animals – the lion, the hens, the kangaroos – take bows, but the jackasses (or critics) have the very last laugh.

David Raymond

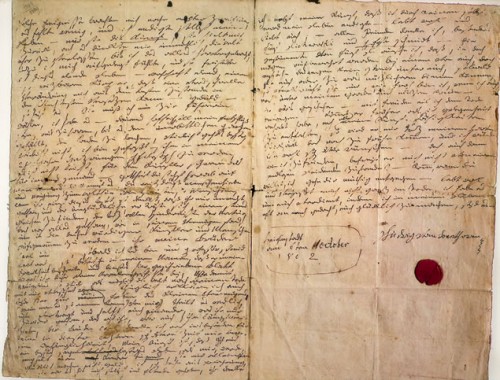

Pages from Beethoven’s despairing Heiligenstadt Testament

Beethoven: Symphony No. 2

If Beethoven’s third symphony is the unbridled crucible of the new Romantic movement, the second symphony is the stepping-stone that allowed him to get there. The symphony was written as Beethoven came to grips with the fact that his ongoing deafness might be incurable. In spite of his desperate state, this was a period of unrestrained vitality in Beethoven’s musical life; indeed the second symphony, dedicated to his friend and patron Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, was filled with humor and contentment.

By 1801 Beethoven sought treatment for his deafness from a number of doctors. A young Carl Czerny, on his final visit to Beethoven, noted “that he had cotton, which seemed to have been steeped in a yellowish liquid, in his ears.” In April 1802, Beethoven left Vienna for the rustic suburb that gave its name to his most famous letter. In the Heiligenstadt Testament, addressed to the composer’s brothers Carl and Johann, Beethoven conveys his utter despair in allusions to suicide, and his desire to overcome his ailment to fulfill his artistic destiny. He didn’t fail to discern the horrible irony of “an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than in others.”

Although this is the backdrop for his second symphony, the music itself is noteworthy not only for its cheer and its sense of irony but also for its scope, unlike any symphony before it. Many of Beethoven’s contemporaries found the Second Symphony long, difficult, and imposing. Haydn and Mozart still owned the symphonic genre: pairs of winds, four movements with a slow introduction, and a rondo finale. For Beethoven, this was his formative contribution.

The Introduction is a slow 33 measures of unsurpassed depth. From the ashes of this opening comes the distinctly mechanical Allegro Con Brio. This opening theme expresses the technical limits of the Classical orchestra as it bristles with gaiety. Beethoven explores this theme, toying with various instrumental combinations, and then setting the whole orchestral beast firmly upon it in triumph.

The Larghetto is a simple song. Perhaps this was Beethoven’s attempt to create a leisurely atmosphere, which was not usually to the composer’s taste. What success! Beethoven captures a sweetness that is truly bold in this movement. As Michael Steinberg, in The Symphony, suggests, “the Larghetto must be one of the most difficult of the symphonic movements in the Nine to interpret…it at first seems to be all A-major smiles, but there is more variety here, even an element of gently humorous capriccio, that most conductors either do not find or dare not play with.”

The third movement marks Beethoven’s most explicit break from the past. Instead of the minuet-and-trio of the Haydn model, this is a scherzo: the young composer “casting immortal” a new orchestral construct. a frank exploration of capricious exuberance. Despite the veneer of youthful zeal, however, Beethoven never strays far from drama, as evidenced by the interplay between the winds and the strings and the august woodwind melody of the trio.

The finale, which was met with shock and awe in 1803, is classic Beethoven before people knew what classic Beethoven meant. As Michael Steinberg points out, “The finale begins with a gesture of captivating impudence, a two-note flick up high, followed by a dismissive growl down below. This has splendid comic possibilities, and Beethoven neglects none of them.” The movement builds on a repeated dominant seventh, finally resolving in a playful coda of false endings that lasts for 150 bars—one-third the entire movement.

To one contemporary critic, Beethoven’s Second Symphony was “a hideously writhing wounded dragon that refuses to expire, and though bleeding in the finale, furiously beats about with its tail erect.” To us now, these sentiments seem close to laughable. In spite of his infirmity, Beethoven sought musical refuge in humor and jollity, and in so doing, redefined a genre. Not bad for a summer’s work.

Andrew Psarris