March is Women’s History Month, a chance to reflect upon and celebrate the contributions and achievements of women throughout history. Women have significantly contributed to the Eastman School of Music and this month we honor the long history of women who have impacted the Sibley Music Library, one of the crown jewels of both Eastman and the University of Rochester.

In the first volume of For the Enrichment of Community Life, Eastman Historian and Emeritus Professor of Piano Vincent Lenti ’60E ’62E (MA) outlines a meeting in 1924 between Howard Hanson, then a candidate for the Eastman School of Music’s first directorship; Rush Rhees, the president of the University of Rochester; and George Eastman, Rochester’s major philanthropist. Rhees pressed Hanson to think about what it would take to make a great music school.

“It will take the life of some man to do it,” Hanson responded.[1]

Although Hanson is credited with building Eastman’s prestige over his forty-year tenure, it was not work he did alone. Nor was it only the work of men.

The Sibley Music Library joined the Eastman School of Music in 1921, occupying the ground floor of Eastman’s main building, and quickly became one of the major claims of Eastman’s reputation. The library currently houses nearly 750,000 items and is recognized as one of the largest and most comprehensive music libraries in the world.

Sibley’s world-class resources and reputation are thanks to the work of the first three visionary women: Barbara Duncan, Ruth T. Watanabe, and Mary Wallace Davidson. Collectively, their tenures stretched from 1922 to 1999. “That’s an incredible history of music librarians that they represented,” says Jonathan Sauceda, current Associate Dean and Head of the Sibley Music Library.

“They were three really illustrious, brilliant women,” says David Peter Coppen, Sibley’s Special Collections Librarian and Archivist.

In honor of Women’s History Month, we profile these three women, along with some of the current women who continue to push Sibley’s legacy into the twenty-first century.

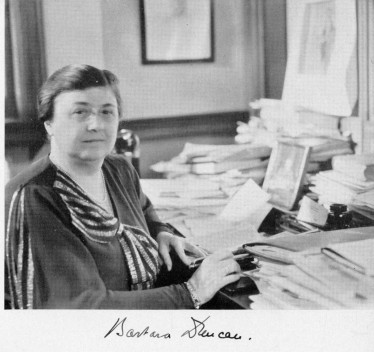

Barbara Duncan (1882-1965): Acquiring History

A nationwide search brought Barbara Duncan to the Eastman School of Music as its librarian at the age of 40, after heading the music division of the Boston Public Library. She came to Eastman with considerable experience negotiating with music collectors.

“Barbara was the ideal person to come because she brought not only that knowledge of music and music history and knew what performers needed,” says Coppen. “But also, because she had this knowledge of working with antiquarian dealers.”

Hiram Watson Sibley, the founder of the library, earmarked $50,000 for Duncan and told her to spend it. “She rolled up her sleeves and got to work,” Coppen says.

“She was going after the really truly historical items,” Coppen shares. “She made six trips to Europe where she was going around to dealers, shops and buying things.”

Among her major purchases was an eleventh-century collection of manuscript treatises known as the Rochester Codex, the oldest item the library owns. In addition, she collected several autographed manuscripts, including the sketch for Debussy’s La Mer, one of the library’s most coveted items. She furnished Sibley with historical manuscripts from the sixteenth through the nineteenth century.

Debussy’s sketch of “La Mer,” one of the treasures Duncan purchased for Sibley Library. Photo by Lauren Sageer.

Coppen says that from correspondences on file, Duncan possessed an unmatched depth of detail on how to acquire, ship, and handle old treasures and had a worldliness about her that helped her engage and befriend dealers.

Illustrative of this was how Duncan was invited to social gatherings between dealers on her trips abroad, which were typically all-male affairs. “How marvelous it was that these men who occupied this very niche field, very specialist field, welcomed Barbara socially and embraced her,” Coppen says. “This was also a woman making her way in what was a man’s world because the top academic library posts at this time were populated by men.”

In addition to Duncan’s success at Eastman, she became a founding member of the Music Library Association and was elected to membership in the American Musicological Society in 1935.

“She really established Eastman and Sibley and the University of Rochester as this really prestigious place early on,” says Sauceda.

“She was the one I think who took the library from where it was in 1922 and pointed it to a very high place,” says Coppen.

When she retired in 1947, the library had 55,000 volumes, enough that during her tenure, the library had to move from Eastman’s basement to a space on Swan Street behind the school’s main building.

Ruth T. Watanabe (1916-2005): Building a Research Library

Ruth Watanabe, a talented pianist with a master’s degree in musicology, was on course to pursue a PhD in English at the University of Southern California when in 1942, her Japanese family was evacuated from their West Coast home and sent to a Japanese American internment camp at the Santa Anita Racetrack during World War II.

Watanabe’s incredible spirit led her to hold huge Sunday afternoon music programs for four-to-five thousand of the other internment prisoners at the Santa Anita Racetrack, at only 26 years old.

“She really sensed that there was this kind of transience, listlessness, and purposelessness in being in these places, and so it seemed like music gave her some structure, whether it was teaching piano lessons on these terrible pianos that were donated or having these big listening sessions interspersed with her lectures,” says Sauceda.

Her family was later transferred to the Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado, where her father eventually died.

A telegraph in 1942 from Howard Hanson inviting her to pursue a fellowship-supported PhD in musicology at Eastman became her ticket out. A former teacher may have tipped him off, but even years later, Hanson refused to tell Watanabe how he found out about her.[2]

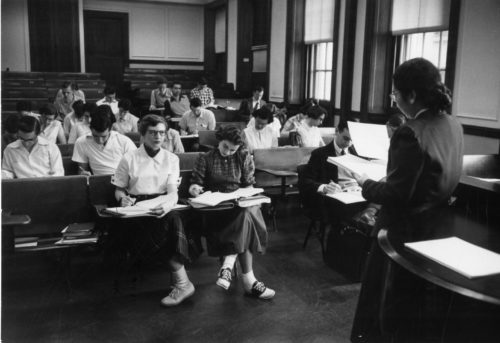

Watanabe needed work to support her PhD studies. She was first hired as head of Sibley’s circulation from 1943–44, and then, Hanson appointed her as Sibley’s librarian in 1947. She earned her PhD in 1952 and continued to teach music history for undergraduates along with her work in the library.

When she started, Sibley’s collection numbered 55,000 volumes. By 1962, it grew to 120,000 volumes of books and scores, as well as 12,000 LP recordings.

Although Watanabe continued Duncan’s efforts to purchase rare materials, she was even more focused on supporting the developing academic needs of the school, which had added advanced degrees, such as Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy degrees in theory and musicology, as well as the needs of Eastman’s ensembles, such as Collegium Musicum and the newly launched Eastman Opera Theatre.

Ruth Watanabe teaching a class at the Eastman School of Music.

“There was a huge industriousness to Ruth because after World War II, things had changed,” says Coppen. “Think about GIs returning from the war, soldiers everywhere, now enrolling in higher education. At the Eastman School of Music, enrollment really went up and demands on the library increased. The library was also called on to collect sound recordings. After the war, sound recordings in libraries were a definite need for education. Ruth established subscription plans with major publishers.”

By the time she retired in 1984, the library held over 250,000 items and was known as one of the premiere research libraries for music in the world. “It’s hard to overemphasize how important a figure she was in music librarianship, not just at Eastman, but really worldwide,” says Sauceda.

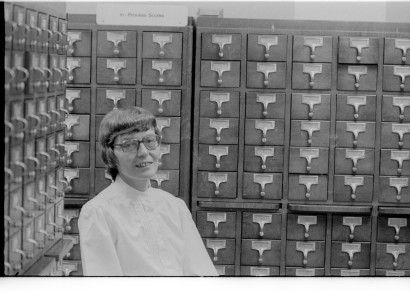

Mary Wallace Davidson (1935-2012): Expanding into the Digital Era

By the time Mary Wallace Davidson began at Eastman in 1984, Sibley Library was already established as a world-class library with an enviable collection. But times were changing, yet again. Libraries were beginning the process of converting their catalogs to electronic form. Davidson led Sibley’s online transition and, in developing appropriate methods, became a national leader in what was called “retrospective conversion,” or simply “recon.”

Due to the size and scope of Sibley’s holdings, Davidson received several grants to hire help converting bibliographic records to electronic form. It was a decade-long effort.

“It was the national leadership that she showed that made Sibley so special, so successful,” says Coppen.

Because Sibley housed such rare and historical materials, many printed on acidic paper known to degrade, Davidson also made conservation one of the library’s main goals. However, space—both to house materials as well as to support conservation efforts—was an issue.

In the mid-1980s, Eastman acquired and renovated the building across Gibbs Street called Eastman Place, now known as the Miller Center. Davidson was charged with working with the architects to design Sibley’s new space, which opened to the public in May 1989. Among several important aspects of the library, such as a special vault for rare items and creating study-worthy spaces, conservation got its own department on the third floor.

“There was kind of a can-do spirit to Mary. ‘Let’s roll up our sleeves, what do we need to do?’” says Coppen.

Several of Sibley’s current staff were hired under her watch. “What I truly appreciated about Mary was that she was so encouraging and supportive of how we wanted to shape our jobs,” says Jim Farrington, Sibley’s Head of Public Services. “She valued our strengths and interests and used them to better the library as a whole.”

Alice Carli: Conserving Resources

Women are not only responsible for building Sibley’s historically unrivaled collections—they also continue to usher the library into twenty-first century success.

Of current women at the library, Alice Carli, Sibley’s conservator, deserves special note. Carli oversees conservation, meaning the physical repair of old, tattered books and scores, as well as the preservation of the library’s current holdings by maintaining and supporting access to items, whether digitally or physically. She manages the library’s conservation lab, the one Davidson built into the plans for Sibley’s third floor in the 1980s.

In the lab, book bindings are scalped, reglued, resewed, and transformed from what she sometimes calls “cornflakes,” acidic papers that have fallen apart into flakes, to durable books able to be recirculated in the collection for student and faculty use.

Photo by Lauren Sageer.

Along with becoming one of the foremost experts on conservation, Carli also reimagined preservation into the digital age. Realizing the potential of scanning technology for both preserving and accessing materials, she landed Sibley its first grant in 2007 to begin to convert over Sibley’s resources to digital PDF form.

What materials qualified? It had to be printed before 1923, it had to be brittle, and something held by no more than two other libraries other than Sibley. Those requirements then expanded to include anything that wasn’t a duplicate and that couldn’t be bought. As of now, Carli and her team have converted over 30,000 of the school’s materials.

Carli and her team upload the files to the university’s digital repository, which ultimately is pulled into the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), a free downloading resource for musical scores in the public domain. Sibley’s contributions are responsible for nearly 12 million IMSLP downloads as of current. They also have started on materials still under copyright, which are put in a special IMSLP repository and await being released into the public domain.

Photo by Lauren Sageer.

“This certainly is one of the things that I feel very proud of, on behalf of all of Sibley, because there was considerable work done throughout the library to make this happen,” says Carli. “And it’s a really cool thing that Sibley has done for the rest of the world.”

Sauceda, the library’s current head librarian, stresses Carli’s influence. “Even if people don’t know her name, if you download something from IMSLP from Sibley, chances are she either scanned it or somebody under her guidance scanned it. She’s had a global impact.”

Carli began working in the library as a student in 1989, while pursuing a master’s of musicology degree, to make some extra money. But she had an interest in book binding and became the binding assistant after graduating. When her supervisor Ted Honea, the library’s original conservator, became the head of rare books in 1995, Carli was promoted to conservator, a job she’s held ever since.

In addition to becoming one of the library world’s experts on conservation, she also wrote a manual Binding and Care of Printed Music, published in 2003 and updated in 2021, which has become one of the major resources for music librarians everywhere. Carli also teaches summer courses through Summer@Eastman, helping librarians and others learn better techniques for conserving printed materials. For more information on Carli’s summer courses, go to https://summer.esm.rochester.edu/.

To learn more about Sibley Library’s history, please see the following resources:

University of Rochester Library Bulletin: Historical Introduction to the Sibley Music Library

Eastman School of Music: About Sibley

Sources:

Bradley, Carol June. “Eastman’s Ruth Watanabe.” Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, Vol. 62, No. 4 (June 2006): 906-925.

Davidson, Mary Wallace. “The Research Collections of the Sibley Music Library of the Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester.” The Library Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 2 (April 1994): 177-194.

Lenti, Vincent. For the Enrichment of Community Life: George Eastman and the Founding of the Eastman School of Music. Rochester, NY: Meliora Press, 2004.

Zager, Daniel. A World Treasure: The Sibley Music Library. Office of Communications, Eastman School of Music, 2004.

*Special thanks to David Peter Coppen for providing sources and photos and for his time discussing the Sibley Library’s history.

[1] Vincent Lenti, For the Enrichment of Community Life: George Eastman and the Founding of the Eastman School of Music (Rochester, NY: Meliora Press, 2004), 115.

[2] Carol June Bradley, “Eastman’s Ruth Watanabe,” Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, Vol. 62, No. 4 (June 2006), 906.