When Emma Gierszal, a DMA student in percussion performance and a member of the Eastman Percussion Ensemble, chose a paper topic for a seminar in Nineteenth-century American Music taught by Professor Michael Anderson, it led her down an interesting path.

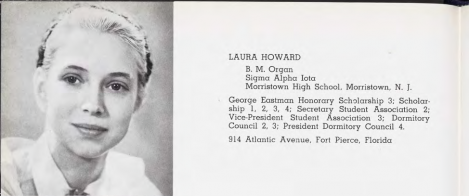

Emma’s interest in ragtime, and some advice from Professor Anderson, led her to the Sibley Music Library, where she found an Eastman master’s degree thesis written in 1942 that has been acknowledged as the first theoretical analysis of ragtime. And unusually for the era, it was written by a female student, Laura Pratt Howard ‘40E, ‘42E (MA).

On reading and studying Howard’s paper, Emma became particularly interested not just in her methods and conclusions, but also in examining the light they shed on what she terms “elitist and racist attitudes in WWII-era academia.”

“It is special that she privileged such a frequently dismissed genre with an academic work,” Emma goes on, but she adds that by 21st-century standards it is seriously flawed. Howard downplays the cultural and musical impact of ragtime, and of the composer we now think of the greatest in the genre, Scott Joplin.

Emma says that “the early 1940s was an interesting time in ragtime study since it was just before the ragtime revival, when ragtime really became known as more of a keyboard genre.”

Emma found that Howard gave analyses of a number of pieces of music according to form, melody, harmony, and rhythm for the theoretical basis. However, as the object of her study, Howard chose almost entirely popular songs of the 1890s; the only instrumental ragtime in her survey is Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag.

Howard agrees with contemporary thought that “authentic” ragtime only came from the southern United States rather than from Black musicians in the northeast, and occasionally takes a superior attitude to ragtime, finding it interesting mainly as a precursor to jazz. Now, of course, ragtime is appreciated as a genre in itself.

Emma adds, “It seemed to me that her main fascination with the genre, however, was its popularity. I believe this is why she looked at ragtime song rather than instrumental ragtime, which was available to her. I think if she truly wanted to privilege ragtime as a precursor to jazz, she would have observed more instrumental ragtime pieces.”

Emma finds Howard’s very presence at Eastman in the early 1940s worth noting. During World War II, the absence of men gave more opportunities for women in higher education, says Emma, so “there actually was a larger population of women at Eastman during this time because of the World War II draft. It was pretty special for the first scholarly study on ragtime to be written by her.”

Pratt went on to a career as a lecturer in music (and a carillonneur) at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. As Laura Hewitt Whipple, she died in 2005.

While Pratt’s musical and historical conclusions are debatable, her paper remains a pioneering effort, and Emma has found it interesting as “a historical artifact [shedding] light on the kinds of misconceptions around race and popular music scholars had in the 1940s.”

Emma will present at this spring’s conference of the American Musicological Society, New York State – St. Lawrence Chapter (NYSSL) as part of the panel “The Social Spaces of Music Education”. Click the link for full information.