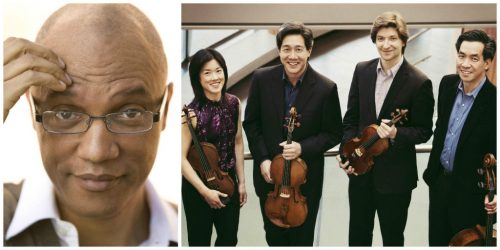

Composer-pianist Billy Childs (left) and the members of the Ying Quartet: Janet Ying, Phillip Ying, Robin Scott, and David Ying

David Ying, who is Eastman’s Associate Professor of String Chamber Music, and Associate Professor of Violoncello, and also the cellist for the award-winning Ying Quartet. He recently spoke to Dan Gross about the beginnings of the Ying Quartet, and his two upcoming concerts; a performance with jazz composer and pianist Billy Childs at 3 p.m. on Sunday, November 20 in Kilbourn Hall, and his solo recital at 3 p.m. Sunday December 4 in Kilbourn Hall.

By Dan Gross

The Ying Quartet started out as a family affair in 1988 at Eastman [with siblings Timothy and Janet Ying on violins, Phillip Ying on viola, and David Ying on cello]. But violinist Timothy left in 2009. What was it like in the early days, and what did you have to do to adjust with new members?

That’s a big question, Dan!

I think we tried hard, all the way from the beginning, to just be a wonderful string quartet, and to not really make a big deal out of the family part of it, to be honest. We didn’t really want any sort of circus sideshow aspect to it, and furthermore, I think most great string quartets treat each other like siblings, anyway. They know each other that well. The fact that we were siblings gave perhaps an extra bond of why we’re together, but in the day-to-day workings of our quartet, when we rehearse a piece, I looked over and saw Janet, my second violinist, not Janet, my sister.

We’ve tried to do that all the way along, and even the way our quartet was known; we’re known first and foremost as a wonderful string quartet, and secondarily, “oh, that’s interesting, they’re family members too.”

I think that lines up well with how you promote yourselves. After a number of violinists, Robin Scott is now in the fold. What does he bring to the table for your group?

Well, the funny thing about having played with Tim all those years is that we developed, obviously as you would if someone was a sibling or not, an incredibly close musical bond. And when you’ve played that long together and someone decides to they are going to retire, and we totally agreed with Tim for his reasons, you wonder what it is going to be like playing with somebody else.

Are we going to be able to achieve the same level of musicality, cohesiveness, and musical interplay? Is that possible? We know that there are a lot of great violinists out here, so Tim is not the only great violinist in the world, obviously; but a quartet requires a very special kind of synergy and communication.

So what we’ve found as Tim left, and we initially played with Frank Huang and Ayano Ninomiya, was first off all, we did appreciate these fantastic violinists. Frank is now the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic, so he’s done nicely for himself; we’re not worried about him. And Ayano is also doing wonderfully well.

We discovered when someone new comes into the quartet, if you’re open to the new sounds and new ideas that come in, it is incredibly invigorating. I think it helped our quartet, Tim’s contributions notwithstanding, to have the new sounds and new ideas, added to ones we developed over the years.

Keeping yourself open to new ideas and sounds has kept this group going for so long. It’s incredibly versatile, and your success is amazing. How did you develop that versatility, and how do you reflect on the success you’ve had?

First of all, know that I’ve been working at Eastman for a while, that an incredibly important part of becoming a improving and successful musician – as I hope all of our students are at Eastman – is not just your talent, but just as important is your level of curiosity. About music itself, but the world the music resides in, and drawing connections about everything in music.

If you don’t have curiosity, you could develop technical skill, but maybe not have anything to do with it! That’s sad.

So I would say that’s a goal of mine for myself as a musician, but for our quartet as well, is that we remain as curious we ever have been about music, and about what is out there, and what we have still to learn, not what just the ground we’ve already trod. I think that attitude towards our work has helped us a lot over the years.

It was definitely, definitely cultivated to a great degree by what we did when we first graduated from Eastman in 1992, which is when we technically became a “professional quartet.” We had a grant that was supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, in which we lived in a rural town, a farm town in Iowa. So if you land there with advanced technical skills or whatever we had learned at Eastman, but no curiosity about the world around you, you are going to have a hard time. Because, the people in that town had very little context for what we did too.

If we’re not curious about each other, nothing is going to happen. And we lived there, it wasn’t just dropping in for a concert. We lived there, so that encouraged us to develop, day-by-day, a relationship with the musical world that we reside in, that has served us well to this day.

And all of your Grammy nominations have been in different projects, you’re not just doing one thing. It sounds like your personal and official success follows this trend too.

Yeah, curiosity is what fuels us, musically speaking. Obviously, we don’t want to do anything that we’re not going to feel comfortable or convincing or compelling in. We’ve tried some musical experiments that we’ve discarded, but when there’s gold to be mined, we don’t let the fact that we’ve never done it before, or the notion that “ a classical string quartet doesn’t do this”, or a “classical string quartet doesn’t play there” — we’ve never let those questions stop us.

I like how you addressed “mining the gold” and getting outside the “classical musicians should do this” frame of mind. Looking at Billy Childs – the artist you’re playing with on the 20th – his music is a melding of jazz and classical. From your perspective, what made you reach to him, and what makes him special as a pianist and composer?

Well, exactly what you’re describing is what made us curious about him! I mean, we started off as friends, we knew of each other the way musicians of like temperament do — they find each other, it seems. Then of course we started talking about what we share in common, what musical projects we share in common, and we wound up becoming involved with him for a number of years. This is not our first time working with Billy

Billy himself — this is not known widely — is a cellist!

No kidding!

He started off on cello, and his teacher growing up in L.A., was one of the toughest teachers that I know of. I was very scared of her. I didn’t even study with her, and I was scared of her. She I think she might have scared Billy enough that became an amazing jazz pianist and composer!

But it didn’t scare him so much that he stopped loving classical string music; he liked to listen to Bartok quartets in his spare time. You can hear all these things in his ear, in his music. It’s fascinating to us! It gives us a way into his world that we might not have otherwise, because I’m certainly not trained as a jazz musician. I love listening to it, but playing it is very daunting, because it seems like such a different language and ethic sometimes to me.

As you’re learning this music, what are some challenges? What are some technical differences and mindset differences between classical and jazz for you?

As you say, the language is different, there are different scales, everything feels different in the hand, but I would say one of the biggest things is that there’s a difference in the way that pulse is felt. Classical string quartets are always bending, swaying, and with jazz or things where there’s a strong rhythm section, it’s a different expression of pulse.

Pulse is an amazingly powerful part of music. It can make you feel totally secure, or it can totally undermine your physical comfort playing an instrument.

Can you tell us what repertoire you’re playing with Billy?

We’re doing some regular quartet stuff: a quartet by Borodin that’s full of amazing tunes, and a great Beethoven string quartet from his middle period, Opus 53 no. 3. I think that’s the way Billy would want it too, I don’t think he wants his music “ghetto-ized;” I think he likes hearing the context of the other music and hearing everything.

Billy’s piece is a piano quintet. In fact, there’s no real rhythm section, so there will be an interesting conversation in our rehearsals about where we go with rhythm. It was great to have him there too. Whenever you have a composer there, it’s fascinating to have a conversation about music.

Can you also give us a little preview of your December 4 recital?

It’s with my wife, Elinor, so also on the Chamber Music faculty here. What are we playing? We’re playing with a great little uplifting American piece to start off with. We’re playing a Kabalevsky concerto for the first time. I see all my students learning music, and I think that I shouldn’t just play the things I’ve played for years, I should put myself to the trouble of playing new music too! So I’m busy practicing right now! And we’ll also play an early Beethoven Sonata.

It’s busy; working hard right now!

David Ying is performing with the Ying Quartet and jazz composer and pianist Billy Childs at 3 p.m. on Sunday, November 20 in Kilbourn Hall, and has a solo recital with pianist Elinor Freer at 3 p.m. Sunday, December 4 in Kilbourn Hall. Follow the links for performance details and ticket information.