Portland (Maine) Symphony Orchestra

Portland is the largest city in Maine, and the Portland Symphony is the largest cultural institution in Maine. With a metropolitan population of about 230,000, the greater Portland area is home to almost one-quarter of Maine’s total population. However, the orchestra draws its audience from well beyond the Portland area, including south-central Maine and New Hampshire. The Portland Symphony Orchestra has been through some difficult times in recent years, as have many orchestras and other arts institutions, but they have weathered the recession with some very interesting and creative actions, and are now on firm financial footing. The musicians joined Boston’s AFM local 9-535, and the entire organization became involved in a significant and innovative strategic planning process.

Brief History

The PSO began its present-day life in 1923 as the Strand Amateur Symphony Orchestra, and played its first concert on Feb. 25, 1924. The orchestra benefited from the backing of a Portland broker, who dropped out of the picture in 1927, when the orchestra became the Portland Municipal Orchestra and found support from the city’s music commission. The orchestra was officially incorporated as the Portland Maine Symphony in 1932. Its first paid conductor, who served from 1938 – 1951, was Bostonian Dr. Russell Ames Cook. In 1952, Richard Burgin, Concertmaster and Associate Conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, became conductor and greatly improved the string section. Rouben Gregorian, Arthur Bennett Lipkin, Paul Vermel served as conductors from 1958 to 1975.

In 1969, the orchestra changed its name from the Portland Maine Symphony to the Portland Symphony Orchestra. Bruce Hangen served as Music Director from 1976-1987. Under his leadership, the PSO developed a national reputation for its artistic quality. In 1980, “Magic of Christmas,” conceived by then-General Manager Russell Burleigh, debuted with guest narrator Margaret Hamilton (the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz – a Maine resident). “Magic of Christmas” continues today to be a major source of income for the PSO, with 11 performances in 2011.

In 1986, Toshiyuki Shimada was named Music Director and he served in that position for over 20 years. During his long tenure, the PSO became committed to youth and family programming, while continually improving the quality of its subscription concert series.

In 2006, Ari Solotoff was named Executive Director and Robert Moody was named Music Director, as Toshi Shimada and Executive Director Jane Hunter stepped down after 20 + years of service. Ari Solotoff left in 2010 to join the staff of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Lisa Dixon was named Executive Director in the summer of 2011.

The PSO performs in Merrill Auditorium, a 1,900 seat performing arts facility located in the Arts District of downtown Portland. The hall also hosts the Kotzschmar Memorial Organ, a celebrated instrument built by the Austin Organ Company in 1912. It was enlarged in 1927, again in the 1990s, and most recently in 2003. The Kotzschmar organ now boasts 102 ranks and 6,862 pipes of varying sizes. Merrill Auditorium underwent a major renovation in 1997. The musicians tell me they are very pleased with the results of the renovation, and love performing in this hall.

Recent Events

The Portland Symphony was faced with significant financial concerns starting in 2003-2004, which culminated in a crisis in 2008. The symphony had begun spending incoming revenue from the following year’s subscription income to pay the current year’s bills, not an uncommon practice in the orchestra world, until the situation become dire. Gordon Gayer, then board president, put the orchestra on a very lean financial diet; they cut concerts, services, and salaries, and decided to embark on a major strategic planning process to chart the way out of their problems.

Simultaneously, some long-time members of the PSO, which had been a non-union orchestra for all its life, decided it was time to seriously start organizing to see if the orchestra could join the AFM and benefit from all that the union has to offer. The musicians voted to join the AFM in the spring of 2008, and they joined ROPA [Regional Orchestra Players’ Association] in 2010. They then proceeded to host the next national ROPA conference in 2011, as a new member.

I was pleased to join many of the Portland Symphony musicians, and colleagues from throughout the country, at the ROPA conference the PSO musicians hosted last August, 2011. I did many preliminary interviews for this spotlight while I was in Portland.

Ann Drinan, March, 2012

Deborah Hammond, Incoming Board President, and Gordon Gayer, Outgoing Board President

When I first interviewed Deborah and Gordon, she was in her first month as Board President, but she has been involved with the Portland Symphony since 1974. Gordon had just spent three years as Board President

Ann Drinan: Where is the Portland Symphony today?

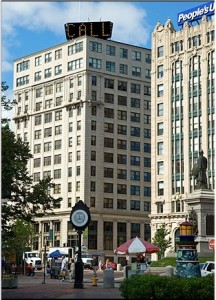

Gordon Gayer: In terms of the community, we are deeply appreciated by a very important segment of our community and we value that. We’d like to be so appreciated that we’re part of the DNA of Portland life. As much a part of Portland as Casco Bay is part of Portland, or as the Time & Temperature Building [a Portland landmark] is. [photo of building here]

Communities are like people and like families – the city of Portland would not be Portland without the Portland Symphony Orchestra.

Deborah Hammond: An important segment of the community was involved last January [2011] in our Strategic Planning process; we had a huge gathering. 65 people braved a snowstorm to be there. The goal was to bring together trustees, staff, musicians, and community leaders for a facilitated conversation about the direction of the symphony at this time. We felt it would be an indication of how well we understood the community. It was gratifyingly easy to get people to participate in a 3-hour meeting.

Out of that meeting came valuable information, and a good number of community members have stayed on and joined our planning committees. The plan was to work in committees through June, and then reconvene the people who attended the January 2011 meeting in late September, 2011 to finalize the plan.

AD: Who exactly was at the January 2011 meeting?

DH: We drew from academia, non-profits, businesses, service organizations, economic development experts, and the tourism development industry.

AD: You’ve described it as a near-death experience; what did you learn?

GG: Financially, we were near the precipice in 2008. We have come to understand that we must tend to our financial state and ensure that we have an adequate financial base all the time. That’s our business. This is as much our business as creating transcendentally beautiful music. And we’ve made huge strides towards building this concept into our own DNA. We need positive operating results – “profits.” And we’ve proven to ourselves that we can do this work. We’ve just ended our third year of finishing in the black, so this is now our habit.

We received a bridge fund of $900,000, which was new capital funding from the community. They really rallied. We also shrank our spending by $700,000 – $800,000.

We have no accumulated deficit, and we will be able to create our own cash reserve. But we must have the discipline to keep it as a reserve. I’m pleased to say that this board and staff are committed to that.

We are sound on a year-to-year basis but, like most orchestras, we don’t have that big security for the decade-in and decade-out view. What we need is a much bigger endowment. [The PSO currently has a $3.2 endowment.] Our annual budget is $2.5 million – the endowment should be 3 or 4 times our annual budget. But we’re moving in the right direction!

DH: In addition to creating an internal line of credit, we made a decision to not spend our future ticket revenue.

GG: When things turned south in 03 and 04, the PSO began to tap into next year’s subscription revenue to pay for the current year. Within five years, we went from taking a little to taking all of it. We used 100% of next year’s ticket revenue to finish the current year. So we decided to stop doing that, and now, all subscription revenue is escrowed.

There were many fears when we did this – some board members had “parking lot conversations” about how the PSO should go back to a community orchestra. Some people felt that Portland could not support a professional orchestra.

So we looked at every unnecessary expense and went after it. We insisted upon a shared sacrifice, we eliminated 20% of payroll, we instituted pay cuts to senior staff and a musician pay freeze, and we decided on a significant reduction in services. We cut every service that was not absolutely necessary, we cancelled our summer concerts, and we reduced rehearsals. We had 20% fewer services. We decided to operate “consistent with our resources.” Another axiom we adopted was “Don’t fund knowns with unknowns.”

DH: Thankfully Gordon righted the ship for us so we could think about the future with confidence. Grants were found, and after Lisa Dixon [the new Executive Director] arrived, we began our planning process. We decided to rethink our mission and core values, identify strategic areas, and ask teams to consider things we were already doing. Our goal was to identify things to keep, things to retire, and things to be tweaked, and we decided to have no more than three initiatives. The teams were: Mission, Programming, Education, Civic Engagement, Telling the Story (building relationships), and Finance (revenue development). We rolled out the plan in September and then out to the January group. We worked in teams until June; then turned to Lisa and her staff to write the plan during the summer. In September, the final product was rolled out to the trustees, and then at a joint meeting of the contracted musicians, music director, staff and trustees, plus the big group of community members that had met in January, so that everyone could be part of the conversation about the evolution of the PSO and its strategic direction.

GG: There’s some dynamite stuff in the plan – both in terms of the keeps and the initiatives. When we developed it, we weren’t sure what would bubble up because of all the resource requirements – money, manpower, time, the Maestro’s vision, the lives of the musicians, the need to work all this into their professional lives. Our mission is to serve the community.

AD: Who facilitated your planning process? Did you have an outside consultant?

DH: John Shibley, formerly with EmcArts and now in private practice, lives in southern Maine, so we were fortunate to have his help. He has done an artful job facilitating this process. He’s different from other planners I’ve worked with and was just perfect for us – he was creative in his thinking, he’s a humanist and is able to put anyone at ease and enable them to speak from their hearts. He’s the opposite of the MBA type. John is an enabler of what’s already there.

John has worked with us all along. He helped develop the leadership role of some orchestra members, and more than once they’ve shifted the direction of the conversation. Their voices have been strong and they have been leaders on the planning teams. And the musicians have a good sense of the community.

AD: How would you describe the relationship of the board and the players?

GG: I cannot overemphasize the importance of the personal contact, of the personal relationship. It’s essential that trustees have some gut feel for the lives led by the musicians and vice versa. Musicians need to have a sense of the lives of the staff and board and other pillars, such as our patrons and stakeholders. Look at the dysfunction that exists among our politicians in Washington, DC – it’s because they don’t know each other.

When I look at dysfunctional situations between players and boards elsewhere, often the money difference is not large enough to justify that degree of alienation.

AD: The Portland Symphony only recently became a union orchestra and joined ROPA. Was this a difficult transition?

GG: Back in 2003-2005 there were some contentious negotiations, and the musicians got some lawyers involved. It was not the peaceable kingdom. But we never had a work stoppage.

The musicians have unionized fully only recently – they are now members of the Boston local. We were a non-union orchestra where the musicians elected their own committee and worked with board committee. We had a personnel book where the players negotiated the terms – sort of like a contract.

AD: What makes the PSO unique?

GG: I’d like to see us as a national model for regional orchestras. We are as good a regional orchestra as any in the country. We have a great hall and a fine ensemble.

Our uniqueness is aided by our strategic plan.

Maine is poor, spread out and economically challenged. Portland has a population of only 62,000. Maine is huge. Yet Portland and Maine support a first-class orchestra.

DH: You could super-impose those six strategic planning teams on any orchestra. We want to build human relationships that sustain us and contribute to our personal lives, but do so in a way that is financially responsible. We must deserve the support we get from the community and we must acknowledge the generosity of spirit and gift.

Lisa Dixon, Executive Director

Lisa came to the Portland Symphony in the summer of 2011 from the Memphis Symphony Orchestra, where she was Chief Operating Officer.

Ann Drinan: You’ve recently completed an in-depth strategic plan. How would you describe it and how have you started implementing it?

Lisa Dixon: The strategic planning process involved over 100 members of the community, both inside the orchestra and beyond. We utilized surveys, interviews, and a tremendous number of meetings held between April 2010 and October 2011 to gather the essential input to help shape the roadmap for the PSO’s future. The resulting plan was adopted by the PSO Board in October 2011, and has already been put into action. It was important to all of us that this process would lead us to a living, breathing document that inspires action, rather than a plan that simply sits on a shelf.

One example of the plan “coming to life” was a pilot Discovery concert for families on October 30, just three days after the plan was adopted by the PSO Board. It was a new concert at Merrill Auditorium with a low ticket price of only $10. The entire event was geared towards kids, with lots of pre-concert activities. Several individuals and organizations came together to provide the funding needed to test this concept from the Strategic Plan, and the concert sold out and was a huge success!

Another idea in the plan came from Nina Allen Miller – a PSO Musician. The idea was to create energy behind the concept that every gift matters – even a $10 donation can make a difference. We decided to test the concept of encouraging a large group of people to each give $10 to help bring another PSO Discovery Concert to life. At our annual Magic of Christmas concert series this year, Robert [Moody] presented this concept (titled the “Candy Cane Campaign”) from the stage. After sharing our aspirations around connecting with kids and families, he made the ask for a $10 gift from the attendees, saying that if just 1 in 5 Magic of Christmas attendees [11 performances in all] gives $10, we will be able to fund another Discovery concert. The end result was another fully-funded Discovery concert for the 2012-13 season – sponsored by this community of $10 donors – and over $40,000 raised from hundreds of PSO patrons!

AD: How would you describe your Board’s involvement with the new plan?

LD: The PSO Board members have been tremendous advocates and contributors to the new direction at the PSO. As part of the Strategic Plan roll-out, we met individually with each Trustee to talk about the specifics of the plan and how they might be able to help and be involved with implementation. With their generous help, we are focused on deepening our current relationships in the community and exploring how to best expand the number of people we’re connected to on a regular basis.

AD: When will you be negotiating with the musicians and what are your expectations?

LD: The contract, which is a 4-year contract, expires this summer (2012), and we have already started conversations with our musicians around our next contract. The last round of negotiations in Portland used an interest-based bargaining approach [IBB] and we are using the same collaborative approach again this time around.

AD: How do you keep the musicians involved in this new direction?

LD: Musician involvement is absolutely critical to our success and is at the heart of the PSO’s future. There are a number of new ways for musicians to be involved through a variety of new committees, projects, or other activities throughout the community. The fifth goal in the Strategic Plan, to increase organizational capacity, articulates our interest in sustaining a highly collaborative internal culture at the PSO. Throughout the season we have been working to find opportunities for musicians, staff, Board, and President’s Council members to all interact and get to know each other. We also have a new Strategic Leadership Team, which includes the orchestra committee chair, the Music Director, the Board chair, the President’s Council chair, the head of the volunteers, myself, and the senior staff. The establishment of this team is an important way to keep communication strong and the whole strategic planning effort alive as we move through implementation.

Nina Allen Miller, French Horn

Nina Allen Miller: I was impressed with the entire strategic planning process but especially the commitment that so many people – orchestra musicians, administration, board of trustees, local community and business members – gave to the process.

AD: You served on the orchestra committee for the New Hampshire Music Festival during their difficulties; congratulations on being elected chair! Can you compare the two situations?

NAM: Had the New Hampshire Music Festival not had such a strong and solid connection with the local Plymouth community, it would not have survived the 2009-2010 debacle. It’s easier for a six-week summer festival to create that kind of rapport – it’s harder in a bigger city like Portland. But it’s absolutely critical to have a personal connection with your audience. We need to be like a sports team – I am familiar with the names and faces of all the players on the Red Sox. A few years ago I attended a Portland Sea Dogs game and, because I didn’t know the players, I really didn’t get into the game.

AD: The Portland Symphony board and management seem very invested in getting to know the orchestra. I know that Carolyn and Lisa are both calling all the musicians.

NAM: In this day and age of less-than-positive orchestra news, it’s nice to have a good story; we’ve received cash bonuses in December 2010 and 2011! The PSO ended those years in the black, so management, along with the Orchestra Committee, worked out a formula, based on salary. This is so indicative of how much they want to work with us, how they value and care about us. It’s a hugely positive and optimistic situation.

AD: Everything sounds great, but I’m sure there are still difficulties.

NAM: Oh sure! – PSO musicians want more services and a raise! It’s been several years since we’ve had either…and it is frustrating.

AD: Is there a divide between the Portland-based musicians and those that come from Boston and elsewhere?

NAM: It shouldn’t matter where you live as long as you show up for work and do your job.

AD: What did you feel about joining the Boston local?

NAM: Great! Something we’ve needed to do for a long time. A very positive step forward for the PSO musicians. I’m very hopeful for our orchestra – we’re a pretty happy bunch, which is not a common occurrence in today’s orchestras. We have a good, strong and solid relationship with the board and management. One of my goals is to continue working on building a bridge to connect musicians to the audience, community, board and management. This vital connection will help to ensure that today’s orchestras not only survive, but thrive.

Carolyn Nishon, Director of Artistic Operations (Click to enlarge.)

Carolyn Nishon, Director of Artistic Operations

Carolyn joined the Portland Symphony staff in 2008. She is a graduate of the League of American Orchestras Management Fellowship program.

Ann Drinan: How is the orchestra structured? How many players live in greater Portland?

Carolyn Nishon: Approximately 40% live in the Portland area, and 60% live in Boston and New Hampshire. We have a few from New York and even from North Carolina. Many have asked me, “Does this create a divide?” We don’t generally talk about a geographical divide – we’re the Portland Symphony Orchestra. We want to focus on supporting this orchestra. The focus is not about where they live, it is about what they create when they come together.

AD: There must be a pay differential for those who live in Portland and those who come from pretty far away. How does it work?

CN: We divide the geography into five zones. Anyone who lives in zones 3-5 gets a hotel room – they pay for half of a discounted room rate. If they share a room, we pay the entire rate for the room. We also pay mileage and per diem by setting rates for each zone.

AD: How do you create a sense of community in the orchestra, given that the majority of the orchestra are “out-of-towners?”

CN: I’m on a crusade to talk to everyone in the orchestra about how to create better relations throughout the organization. Not just on a business level but also socially. How do we get to know each other better? The hotel creates a space for some musicians to congregate and socialize. I continue to think about what we can do to create more space for everybody to come together.

I’m in a brainstorming phase, and I intend to talk to each player about this. These conversations are giving me a much larger sense of the ebb and flow of the PSO’s history – of the musicians’ feelings about the PSO in terms of when they joined the orchestra.

AD: Setting up your rehearsal schedule must be a bit of a nightmare.

CN: The rehearsal schedule is a puzzle. It used to be more consistent before we had our financial crunch. For the Tuesday evening concerts, it was uniform. The previous Music Director, Toshiyuki Shimada, was here for 20 years and he lived in Portland. In contrast, Robert Moody also conducts in Winston-Salem, NC, and he does the Arizona Music Festival.

If people are driving every day, it’s a lot cheaper to condense the rehearsals. The schedule varies greatly now. We did a survey last year about scheduling preferences. There’s a large spectrum of opinion amongst the orchestra players – we’ve tried to represent as many preferences as possible while staying within our financial means.

AD: What does a week’s schedule look like?

CN: For a Tuesday evening concert, we’ll often have a dress rehearsal Monday night, two rehearsals on Sunday and one on Saturday. Or sometimes we have two rehearsals on Sunday and two on Monday, but this is a problem for school teachers. For Sunday afternoon concerts, we generally have two rehearsals on Saturday and one on Friday night. Currently, the first and last concerts of the season are doubled (Sunday and Tuesday performances) – we start rehearsal on Thursday and have Monday off.

Robert is programming them as opportunities for great music. But there are so many remaining questions: Do we need to define our classical series? What does it mean to double these concerts? Is a day off in between a good thing? What about a runout? Are there donor opportunities? Obviously there is a lot of of planning going on.

AD: Tell me about your oh-so-successful Christmas concerts.

CN: Bruce Hangen began “The Magic of Christmas” over 30 years ago as a single concert, and it grew over the years to a maximum of 15 concerts. So many people come from all over the state of Maine and the region – it’s their tradition for the holidays. It’s almost like another endowment for us – these concerts bring in a great deal of our financial income. Since Robert arrived, we have added more production aspects to the show – dancers, larger than life puppets, and aerialists flying over the orchestra.

There are many opinions about what the “The Magic of Christmas” could or should be, but in Robert Moody’s programming, the concert has three different segments: the traditions of Christmas, the story of Christmas (the Nativity), and the spirit of Christmas.

Radio City was performing in Boston in 2010 and there were special Amtrak rates to get to a show. But our shows were very well attended despite the competition. The people who live in Maine are really into “buy local” – they’re proud of their state and what it has to offer.

AD: How do the musicians get along? Is there a Portland/Boston divide?

CN: There’s a real sense of family in the musician community. They’re a tight group, dedicated to Portland. And they have a lot of stories to tell.

AD: What was it like when the orchestra voted to join the Boston local?

CN: They were operating under a contract but the players wanted to have the expertise of the union at negotiations. Many of our players are Boston musicians and some were concerned that they might not able to continue to play in Portland if it remained a non-union orchestra.

AD: I understand you used an IBB [Interest-Based Bargaining] approach.

CN: In 2008, negotiations had already begun when I got here. We worked through the IBB process with help from Doug Stone and Gillien Todd at Triad Consulting Group in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There had been a big training session before I arrived. Three months later, we were unionized. The local officers had not gone through the training and the Orchestra Committee personnel had turned over, but the spirit was still there and the facilitators stayed. We were working with difficult issues, we were not sound financially, and then the economy tanked. Collectively, we understood that we all had to work together in order to keep the orchestra alive; this unified us and brought us together so we could look at what we needed to as a team. Our current contract expires in 2012, so we are currently in negotiations. We continue to use the interest-based approach.

AD: How has the CBA and the way in which you negotiate evolved over the years since you began at the PSO?

CN: When I began here at the PSO, the contract was a printed Word document; outlining the group’s interests. Restructuring the document and putting the contract into its current booklet form was a big step for the PSO. During our negotiations in 2008, a pivotal meeting happened where the Chair of the Orchestra Committee, Richard Kelly, said, “I’m going to tell you what it’s like to be a musician – a day in the life.” There were board, staff, and musicians in the room – it’s a large committee. He talked about who he is and where his interests come from. The board members found his talk inspiring, and in turn, each board member talked about why they support the PSO. It was a pivotal meeting in aligning where we were all going.

AD: How would you characterize relationships now, in terms of negotiations and strategic planning?

CN: We’re still working towards attaining true financial health, so we can give the musicians the service pay they deserve. By taking the time to get to know each other, we created a trust. But I’ve always felt that I’ve had relationships and trust with both chairs [Richard Kelly and Tony D’Amico]. I talk to Richard every week; together, we discuss musician feedback, comments, questions and concerns in order to improve the overall functioning of the orchestra. Of course, we run into bumps now and again, but now we’re all in it together. It is important to be transparent, open and candid.

The strategic planning process has involved the musicians, so the conclusions are represented by all parts of the organization – board members, staff, musicians, volunteers, and community members. So we need to use that parallel structure in making our decisions. We’re telling the story of what we’ve done through this process. That’s the only way the whole organization can move – if there’s understanding and if time has been put into the process.

My relationship with the Orchestra Committee chair is one of the most important ones for me – we are two sides of the same coin. We’re coming together to communicate about what’s happening from both perspectives. We come together and go back; it’s an open line of communication. We can be honest and candid with each other.

Richard Kelly, Orchestra Committee Chair and Percussionist

Ann Drinan: I understand that the Portland Symphony joined the Boston local and ROPA just recently. How did this come to happen?

Richard Kelly: We came out of negotiations six years ago and we didn’t know what was going on. We were concerned about the direction we saw the organization going. Then a process of inviting us to join in discussions with the board started three years ago. Our involvement was much more in-depth – we were a voice that they would have to listen to. Before, we had a seat in the room but we never got reports back and lacked some understanding of the organization’s goals. It’s now in our bylaws that players who serve as board reps must do a report after each of these meetings, so the orchestra members know what’s going on.

AD: What was the reaction of the musicians to the unionization process?

RK: It was a cultural shift in the orchestra – musicians are smart people but they’re busy people. Communications between time-crunched musicians is tough. Bob [Couture, musicians’ representative] and Pat [Hollenbeck, President of the Boston local] said, “The smarter we are, the better we’re going to negotiate.” We did our homework – we were well read and well rehearsed. We weren’t just a unified front but we were also being intelligent about what we were saying. We could question intelligently and refute what they said based on the hard numbers and the homework we did.

The best thing that happened in our negotiations was one particular meeting. We were looking at musicians’ cuts, and we didn’t know the staff salaries but took a guess. We talked for four hours with a red marker on a white board, and (I) announced, “This is what we think you’re making.” By the look on the former Executive Director’s face, we knew we were close. They asked for a caucus, and they came back and everything was different. “So what do you want?” they asked.

It really was the act of becoming educated. We didn’t back down. These are hard numbers, and we were pretty darn close to disaster. Then they realized they were dealing with an educated group.

AD: How did the vote actually happen?

RK: There were seven of us on the Negotiating Committee; I was the chair. Tony [D’Amico] was in charge of the unionizing committee. The Orchestra Committee at the present time was comprised of wonderful people but they were very cautious about all the changes appearing to happen. A vote to join the union was being postponed based upon these feelings. So I took the roster and went through it, and then I went and talked to people one by one to see what their thoughts about unionizing were. I counted the votes during a rehearsal and in the middle of the rehearsal, I knew we had the vote. Two months later we went into negotiations with a signed union letter.

Help from the national was offered for our upcoming negotiations. But Portland is a unique orchestra made up of a tremendously diverse group of freelancers. Since we understood this culture best, we thought we should handle the process. The Boston local then offered all of its support and helped us get a plan together.

It was decided that I could be a voice in these negotiations. We had an agenda for every meeting, and we stuck to the goal for the day. Bob was always in the room for each session but he let me speak on behalf of the orchestra. This relationship with the Boston local helped to forge a relationship with the PSO musicians and helped us gain an identity as a legitimate bargaining unit. We had the local’s support when we needed it, but it still felt like negotiations were being done in-house – this created a strong sense of community.

AD: Carolyn explained your schedule to me – it sounds very complicated.

RK: Our schedule didn’t change for 20 years – we had one Saturday and two Sunday rehearsals, a Monday night dress, and a Tuesday concert. So most teachers had no conflicts. Robert Moody now goes to two Sunday rehearsals, two Monday rehearsals, and a Tuesday concert, or a Thursday and Friday evening, Sunday afternoon, and Monday afternoon. They’re putting rehearsals all over the place, which means that many of us have to get out of a rehearsal or cancel the whole set. We used to have Sunday rehearsals at 10 and 2; now they’re at 2 and 7.

AD: What does the orchestra think about all these changes?

RK: The committee did a survey, and it was pretty clear that most of the orchestra did not like the doubles on Monday and wanted the earlier doubles on Sunday. And when the Boston Philharmonic has a Sunday afternoon concert, it wipes out our brass section.

AD: Do you feel that there’s a divide between musicians who live in Portland and those who come from NH and Boston?

RK: We touched upon this in our last negotiations – Portland residents vs. the commuters, and who gets travel and hotel pay. Over the years, we have received such low pay that some of the musicians might see travel as part of their base pay. Now the base pay is at $94, so the commuters are making $140, but the local folks are only making $94. But commuters are now paying very high prices for gas and have more car expenses. So I feel that the orchestra has come to realize that we are diverse and many players have different needs.

AD: Tell me about your conductor, Robert Moody.

RK: He was overwhelmingly the #1 candidate for the job; the orchestra fell in love with him. He was energized, the orchestra sounded great, he conducted from memory, and the vibes were incredible. Ticket sales rose, and the audience loved him too. Our previous conductor was with us for a very long time, by today’s standards (20 years) and was ready to move on. There was also a big a turnover in management at this point, and better musicians were joining the orchestra. We needed a conductor that would help the orchestra grow.

But we’ve had some challenges with him. He attempted to “discipline” some players but didn’t handle it very well, according to our contract. He needed to learn the language of our contract first before any actions were initiated. So some members of the orchestra gave him little interaction this year. To make amends, he had a pizza and beer party at his house – but he did it on a Sunday night when 60% of the orchestra had to get back to Boston. Robert is used to dealing with his musicians in Winston-Salem. In Portland our contract is now what needs to be learned and followed.

AD: Has having a union contract made a difference for the orchestra?

RK: We had one grievance this year about an overtime situation, but it got resolved. The biggest thing we notice is that the quality of the orchestra is getting better and better. Now that our audition ads are in the AFM’s International Musician, we have fantastic new players. Since joining the union, we had auditions last fall for violin and percussion. People came from all over. We had 2-3 days of auditions for section violin, and 30 people showed up for a 3rd percussion audition. They were all very high caliber.

Robert Moody, Music Director

Robert Moody became Music Director of the Portland Symphony in 2008. He is also Music Director of the Winston-Salem Symphony and Artistic Director of Arizona Musicfest.

Ann Drinan: What is your sense of the role of the orchestra today?

Robert Moody: I think orchestras remain the vital centerpiece of cultural life in any city. But the orchestra must change and evolve in the 20th century or it will be dead.We must keep the life and health and relevance of our orchestras in our communities. We can do this by putting the musicians and the music first, of course. But also by really listening to the voices of our diverse community, and making sure our programming, and the way in which we present programs, is completely relevant

AD: Can you be specific about the Portland Symphony and the Portland community?

RM: Portland has a wonderful sense of identity with its orchestra – more than many other cities. The average person on the street will say “my” symphony rather than “the” symphony. I’ve spent great amounts of time in other communities, and can state that the Portland community is much more vocal about their orchestra than many peer cities. I hear about our programming here more than anywhere else – the audience tells me what they like and what they don’t like. This helps me get a sense of what programming is right for Portland.

This community and these musicians are very good at alerting me to the overall perspective of the community regarding artistic output. If there’s a feeling in Portland, I’d say they lean a bit towards integrating classical music with other forms, as opposed to an “ivory tower” approach. What audiences in Portland will not stand for is any type of programming that they feel is “dumbing down” the musical experience.

Perhaps that tendency is because we’re close to Boston. Many Portland patrons have BSO Friday morning subscriptions, so this experience probably adds to this group’s being so well informed. But there’s also a pride in Maine and a pride in “what’s ours” that leads to a loyalty towards the home orchestra.

The Portland Symphony is 86 years old. We’ve had our ups and downs financially but not artistically. The community has never pulled back from supporting the orchestra artistically.

AD: What is your relationship with the management and the board?

RM: A board will hire a music director for his/her initial chemistry and that sense of buzz at the beginning, when everyone gets excited. Here in Portland, there was a lot of buzz when I was hired, especially considering that my predecessor had been here for 23 years. I’m still enjoying that new era feeling, but after the board hires a music director, they keep him on for his programming and how he brings it to life.

Lisa Dixon {Executive Director] is a superstar – she’s fantastic. I felt slightly sickened when Ari [Solotoff ] left (he’s in Philadelphia now as Executive VP to Alison Vulgamore). Ari really knew how to fix our problems; we had a great “dynamic duo” going on. He came up with a plan to get this orchestra out of debt; we went from a debt of $400,000 one year to a surplus three years running. But Lisa stepped in seamlessly, and has continued to lead the orchestra in a way that will keep us fiscally sound as we pursue greater artistry.

In the 21st century American orchestra, the music director must play an equal role with the CEO; they must work hand in hand, behind closed doors, and then leave the room with a unified voice. They must agree simultaneously not to hurt the artistic quality of the orchestra and not to live above their means. We certainly don’t need a Boehner-Obama debt-ceiling fight. Together we had to establish the procedure of not using next year’s money to fund this year, and not using the endowment as an ATM machine. We can conjure up new programming and come up with exciting new ideas. And we want to raise the number of services and pay for the musicians. But only when it’s guaranteed that we can pay for it.

AD: How did the organization decide on hiring Lisa when Ari left?

RM: Gordon received two calls on the same day – one from Ari and one from me. Both of us independently recommended Lisa. I had guest conducted in Memphis several times and had gotten to know Lisa, where their CEO, Ryan Fleur, was singing her praises. She was the force behind making the right kind of positive energy and synergy between management and players in Memphis. We wooed her heavily; we hired Cathy French’s search firm and Lisa came to the top of her list as well.

AD: I understand you’ve gone through an intensive strategic planning process.

RM: Last summer we finished the initial process of strategic planning – and it feels like we’ll really follow this plan. Everyone, musicians, staff, board, volunteers, came together to work on our problems. There was constant conversation regarding “all of us have skin in the game” at every meeting, as we are all stakeholders in this organization. We’re in the same boat and it sinks or sails by how well we man the ship. The music director cannot be an ivory-tower character – he must include himself in the process. The musicians can’t just show up and play – they also have a grand responsibility in this process.I say to them, “You started this – you got together 86 years ago. We need to always honor that feeling of groundbreaking creativity and community devotion.”

No one should have a sense of entitlement – we should all have a sense of investment. We have good honest discussions, which are sometimes hard. I had to go to a board meeting and explain to them that the amount of money some of our patrons might spend on a garden party could be equivalent to a year’s salary for a per-service musician. Many of the musicians are “driving for dollars.” They play for us in the PSO, plus numerous other orchestras in the Boston area, in Rhode Island, in New Hampshire. They teach at universities, at public schools. They teach private lessons, play weddings, funerals, and bar mitzvahs … you name it. Sometimes it’s easy for the board or audience to see a player in his “white tie and tails” and make assumptions, not realizing that the tails may well have come from a thrift shop.

AD: What is your relationship with the orchestra players?

RM: We have a grand relationship. I feel that the chemistry of the first audition concert still exists. We have had some difficult growing pains in our four years together, but in the end these pains have led to a stronger relationship. There are parts of the job description of a music director that aren’t pleasant. But I have to own those parts just as I own the incredibly rewarding parts. At the end of the day, most musicians would say, “Yeah, it wasn’t fun but that’s also his job.” The worst part of my job is when you do have to discuss a player’s tenure in the orchestra – you must do it privately and with as much respect for the human as possible. I’m always looking for a solution that can be a positive solution.

AD: What is your vision for the Portland Symphony?

RM: With regard to programming, my vision is finding interesting threads of connection between the works on one program. The concert experience is a journey; the musicians, the conductor and the audience are all on the same journey. We often have 2,000 people in Merrill Auditorium (including the performers); that permutation of humans gathered together will have never been exactly that way before, and will never be exactly that way again. So whether it’s Beethoven’s 5th Symphony or the music of a living composer like Mason Bates, it’s a live music journey. That’s what we have to sell. I like to present interesting threads that the audience members might not otherwise see. And I like to think outside the box. For example, I did a concert themed on Italy with the Mendelssohn Italian Symphony, and pieces by Barber and Bates, who were both Prix de Rome winners and wrote these pieces in Italy.

I’m always looking for ideas to answer the question, “What’s next in music?” We’ve explored western Europe and Russia, done a lot with North America but not so much with Central or South America, and very little of Africa or Asia. So a few years ago we performed an African drumming concerto with four Senegalese drummers, paired with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

I’m also interested in collaborations that are atypical. We also recently performed a piece called Headcase – at age 28 the composer, Brett Dietz, suffered a stroke and lost his ability to speak, walk, and write. The piece is about his recovery. The Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble commissioned the work, then Detroit performed it. Portland was the third performance. We collaborated with Maine Medical Systems – Brett went to talk to stroke victims and their families. During the performance we had a screen showing some of his MRI scans, with audio clips of him learning to speak. I’m constantly looking for some way to collaborate in unexpected partnerships. Another example is Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet with four actors interspersed between the movements. I like to experiment.

Tony D’Amico, Bassist and former Orchestra Committee Chair

Tony is a member of the Boston AFM Local 9-535’s Executive Committee. Tony was Chair of the PSO’s Orchestra Committee when we had this conversation.

Ann Drinan: How would you characterize the Portland Symphony? You live in the greater Boston area and play with several other orchestras.

Tony D’Amico: Each orchestra has its own personality. I play in the Rhode Island Philharmonic and the Springfield [MA} Symphony. Portland is definitely the most homey. People have played together for a long time, and we’re a close-knit community. We even have a knitting circle in the break room! There have been lots of marriages (and a few divorces) within the group.

The atmosphere in another orchestra I play with is somewhat uncomfortable. I’ve played in that particular group for15 years and there are still some people I don’t know, whereas in Portland I know everybody and can have a conversation with anybody. We’re a friendly group, it’s a terrific town, and I love going up there. The Mainers appreciate the Boston players’ coming up. We used to have 120 services/year, so you could get a teaching gig and have a comfortable life in Portland. Now we’re down to 72 services/year. In fact, we had a re-opener in our contract and this was the sticking point – we need more services. We insisted that management not give us a $3 raise and at the same time wipe out two services.

AD: Describe how the Portland Symphony came to join the Boston local.

TD: The people of Maine have an independent streak. We heard players complaining about why can’t we do this or why can’t we do that, but whenever we talked about joining the AFM, they shied away from it. And I think they didn’t want to pay the work dues.

One year, money got tight, and we had a difficult contract negotiation. Things got kind of ugly. Negotiations used to involve just the general manager and a few musicians. This time there were lawyers in the room, and we had to collect funds from the players to hire our own legal counsel. That’s when some of the leaders in the orchestra, who’d been in the orchestra for a while, said that maybe it’s time to unionize. I picked up on it right away. I’m an officer in the Boston local [local 9-535] and I knew that I really shouldn’t be playing up in Portland, but the AFM looked the other way. At that time, about 50% of the orchestra were also members of the AFM.

I talked to Barbara Owens, who was then president of the local and a great help in this whole process, about the situation, and she advised that we should feel it out and see if there’s enough support to make it happen. We also talked to Janice Galassi [of Symphony Services at the AFM] who showed us the path that the AFM has put together for organizing. She advised us to put together a small group of players who trusted each other, and quietly ask around to see what the level of support for unionizing was. If you make a big announcement, people will shut down and not consider the option.

I went through the orchestra roster and selected 5-6 people who were pro organizing and who were also leaders. I chose both Mainers and Bostonians, strings, winds and percussion, and asked them to be on the organizing committee. Then we all ranked the players on the roster from 1 to 5, where 1 = most interested and 5= anti-union. We decided to get cards signed by the 1s and 2s. Once a certain percentage of the group has signed cards, you’re protected by labor law. At this point, management can’t do anything when you tell them you’re starting an organizing campaign.

PSO Bass Section (Click to enlarge.)

AD: How did people react to your organizing “behind the scenes?”

TD: Some people were upset; I’ve heard people rumbling about organizing since the early 1990s. I just wanted to call the question and get it out in the open. Then we could tell the players that we’d get all the answers to their questions.

At one point, I pulled Ari [Solotoff, former executive director] aside; he did recognize us, but he thought things would be easier without the union. And I hasten to add that Ari was not involved in the bad negotiation. I explained to him that we were thumbing our noses at the local in Boston, because half the musicians in the orchestra belonged to the Boston local. I also explained that unionizing could end up serving and helping him; the orchestra has a great hall, we sound good, and we live down the street from the #1 recording mastering engineer in the world, Bob Ludwig. I explained how we could record the orchestra without the fear that the AFM members would be penalized by the union.

Finally we had enough signed cards, we had them verified independently, and Ari chose to recognize the union based on these results. He could have insisted on a vote but he chose to recognize us. We then negotiated our first union contract, with Richard [Kelly] as Chair. Any hard feelings have all faded away, and for the most part the players seem happy that we organized.

AD: I heard that you had a confrontation with your music director about a few of your colleagues.

TD: Better communication between the music director, management, and the orchestra committee before all that took place would have avoided a lot of heartache. The incident shook the foundation of the players involved. A little sensitivity would have gone a long way to avoiding that. But it’s difficult to get that genie back in the bottle once it’s out. We were all pleased to have the support of the local during that time. It made us look good that we did the right thing at the right time.

AD: What are your impressions about your management?

TD: Our management team have good hearts and I truly believe they want what’s best for this orchestra. We operate as “partners” because we want the same things from different sides. Lisa [Dixon] shares the same philosophy. As chair of the orchestra committee, I have an excellent working relationship with Director of Artistic Operations Carolyn Nishon. We have a weekly phone meeting to discuss any issues that might be bubbling up.

Gordon [Gayer, the previous board president] needed to make sure the orchestra stayed in the black during some difficult financial times; he needed to make some tough decisions. But I always felt that I could call him, suggest we talk about an issue, and then fix it together. I’m happy to say that the orchestra is in fine financial health now, thanks in no small part to his leadership.