by Peter Folliard

Eastman Philharmonia presents its second free concert of the semester this Friday night at 8 p.m. in Kodak Hall. The program opens with Beethoven’s tragic Coriolan Overture conducted by second year DMA student Peter J. Folliard, and concludes with Beethoven’s heroic Third Symphony. Contrasting quite perfectly, Maestro Varon programmed Mahler’s Rückert Lieder with master’s student Alan Cline.

It’s difficult, after we’ve become so familiar with the scores of Wagner, Strauss, and Mahler to make Beethoven’s music sound as alive and fresh as ever. With ninety-nine years between the Rückert Lieder and the “Eroica“, Maestro Varon has worked with the orchestra and his graduate conductors to bring all the vitality that is in Beethoven’s score to the stage.

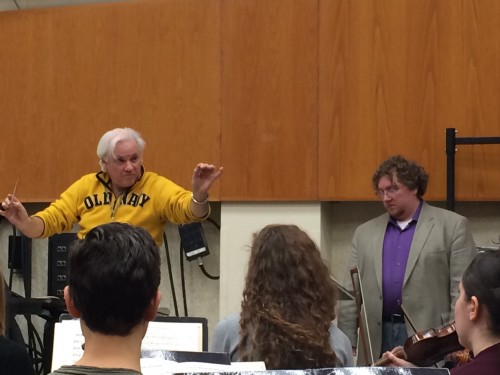

Maestro Neil Varon discusses Beethoven’s orchestration with second year MM conducting student Garrett Wellenstein.

The orchestra has worked to find its own voice for Beethoven, with a focus on sound and control of tension through a deeply unified rhythmic pulse. But the notes and the rhythm are only a piece of the puzzle. Maestro Varon has been acutely attuned to Beethoven’s dynamic and articulation markings. The second movement, Marcia Funebre, was the focus of an entire rehearsal, and its first three notes received at least five minutes of extra attention. But this is what makes Eastman’s Philharmonia exceptional, and this performance not just another performance of Beethoven’s “Eroica.”

Meet the concert’s vocal soloist, and hear his thoughts on Gustav Mahler’s Rückert Lieder:

Alan Cline is a second-year Master’s student in Vocal Performance and Literature in the studio of Jan Opalach, and formerly of Robert McIver. At Eastman, he has appeared on stage as Charles Webb in Rorem’s Our Town and as the Bass-Baritone in Glass’ Hydrogen Jukebox. He is also an active soloist in the greater Rochester area, including appearances with Voices, First Inversion, and the Genesee Valley Orchestra and Chorus, as well as the Eastman Repertory Singers and members of Collegium Musicum. Mr. Cline was recently awarded second prize in the 2015 Jessie Kneisel Lieder Competition and third prize in the 2016 Friends of Eastman Opera Competition. In the coming months, he will appear as Count Almaviva in Eastman Opera Theater’s production of Le nozze di Figaro.

Conductor Neil Varon and baritone Alan Cline rehearse Mahler’s Ruckert Lieder

Alan’s perspectives on Mahler, song, and music:

There are so many people in our time who believe that “Classical Music” is a thing of the past that deserves to stay in the past. Many argue that music by old, dead, white men just isn’t in touch with our ultra high velocity lifestyles in the 21st century. If you take an “ultra high velocity lifestyle” glance at it, it may appear that they are right. But when one takes a moment to look deeper, we realize that we need this sort of music more than ever. Mahler and his writing can provide a nearly perfect remedy to what ails us in today’s world.

When someone mentions Gustav Mahler’s name, the first thing that springs to mind may be the symphonies. And this makes sense; the man spent most of his professional life as a conductor and one can imagine he would be well versed in telling a story through an orchestra. We know that Mahler was actively conducting voices as well. He held posts for years as director of various important European opera houses and even had a brief stint at the beginning of the 20th century with what we now call the Metropolitan Opera. Yes, that Metropolitan Opera.

Whether it was for the love of singing, the love of the poetry, or the love of the music that was written in the genre, Mahler knew well the power of storytelling through the human voice. With all these facts in place, it may be argued that opera is the ultimate storytelling and music delivery method, combining the beauty and power of the human voice, the visual mastery of stagecraft, and the might of the symphony into the 800-pound gorilla of Western Art.

There is, however, a slight problem in this argument, although many hold it as universal truth. In a society such as ours, when couples can rarely get through ten minutes at a dinner table without use of their phones, how can we expect people to sit through a three-hour operatic production? Of course, there are still droves of music fans and musicians that happily cram houses to see La bohème or Carmen, but the masses still may argue that this is not an accessible art form. What we need then is something that combines the power of the voice and the might of an orchestra and presents it in a beautifully wrapped, bite-sized form. And this, friends, is what Mahler has done.

While symphonies can deliver a massive story with a million emotions tied into it, the art song provides what can perhaps be described as a snapshot; a mere second in time, or a single moment of exquisite emotion that transcends time and affects the core of our being. And I believe truly that Gustav Mahler knew this. So he selected these texts of Friedrich Rückert, set them to music so that they could still be delivered by the human voice, and accompanied them with a symphony orchestra to create an emotional experience that allows us to gaze into the soul of the poet, the composer, and those who choose to share their vision through performance.

This is what our world needs more than anything. Now, we as a race have forgotten how to express our emotions through healthy means and resort to violent acts that tear apart families, cities, and nations. We have lost sight of the beauty in the world that draws us together and we have forgotten how to enjoy it together. Perhaps if we can all stop for just a few minutes and enjoy the beauty of humanity together, the world would be a better place. This small piece of humanity that Gustav Mahler has committed to the ages and the we are honored to share holds the power to change lives for the better. And all we have to do is stop and listen.